Between belief and disbelief, certainty and uncertainty, trust and distrust lies doubt. Doubt can be deliberate questioning or a state of indecision, resulting in a reassessment of what reality means or a paralyzing suspension between contradictory propositions. An uncomfortable condition, as Voltaire observed, but preferable to certainty, which is inherently absurd. Or some surprising gap stretching intellect and emotion, resulting in delight. Join us in this intriguing gray area as we prepare our Winter 2013 Doubt issue.

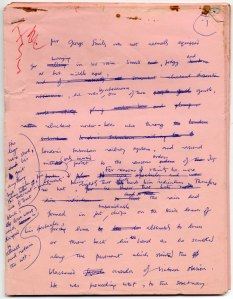

A page from John le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy pink manuscript detailing George Smiley’s character development (Source: Bodleian Library archives)

I admit it: I’m a terrible literary snob. I cannot countenance fiction that has no literary value. When pressed to specify what I mean by that, I continue in the negative: stories that remain unread–particularly by me–have no literary value. And add that for what seems like forever, I’ve been picking up and putting down novels and short story collections plucked from lists prepared by prestigious organizations such as the Nobel Foundation well before reaching the point of no return, mentioning that my sole consolation since going all-electronic is I can do so at half the cost.

If forced to reflect further, I have to admit that after I’ve turned from some highly touted title I tend to turn to something that meets one of my mother’s criteria for what constitutes a good story: a minimum of one dead body discovered within the first 15 minutes of the opening lines. Sometime in the Sixties, after someone writing under the name John le Carré introduced me to a character called George Smiley in The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, I had come to see that–given a little leeway–at least on this one thing she was totally correct.

Soon I was not only revisiting spy fiction classics such as Somerset Maugham’s Ashenden: Or the British Agent, which my father once read, but also devouring crime and detective fiction, which the other men in my life kept leaving around. At first, I only read what was readily available: novels by Raymond Chandler, John D MacDonald, Rex Stout and such; now, I seek out works by the likes of Henning Mankell and locals such as Laura Lippman.

That puts me on a par with the rest of the world. A list of best-selling authors shows the two front-runners, Will Shakespeare and Agatha Christie, in a dead heat at an estimated two to four billion copies apiece, even though the latter got a late start. Notable also-rans include Georges Simenon, who beat Leo Tolstoy by a good bit, Jeffrey Archer, who snuck in ahead of Charles Dickens, and Mickey Spillane, who soundly trounced Hermann Hesse.

Seems to me that something more is going on than merely the telling of compelling tales. Something that taps into our innate sense of how little we know of the world, of the mysteries of life and death and how even small attempts at understanding–with all the doubts that they raise–can result in sheer pleasure. To see if that made sense, I asked local writer Austin S. Camacho to elaborate on the subject, which I share with you here:

Doubt is generally considered to be a negative emotion, a feeling that can suck the joy out of our personal lives. However, in the fictional worlds to which we love to escape, doubt is a necessary element. This is all the more so in a good mystery story, where the natural order of a seemingly sane and stable world that has been thrown into chaos serves as the foundation. Our hero or heroine must then strive to restore that order: find the murderer, catch the thief, locate the missing person.

At one time, a writer could introduce a deus ex machina–a contrived and unexpected intervention of some outside force–to bring a story to its happy ending. For modern readers, a story is a disappointment if it becomes too obvious who the villain is or if it seems inevitable that he or she will be brought to justice. On the other hand, if it is clear that the bad guys will get away with murder, well, that is no fun either. The outcome must be left in doubt for the tale to pull us along. This gives us a chance to get involved, effectively trying to help the hero or heroine find the answer.

We become engaged because of doubt, which imitates our own lives. Fear and doubt often travel together. Like a roller coaster ride, we get into a good mystery because of the thrill of unexpected twists and turns. If there has been a murder, we come to doubt every character for more than one reason. First, everyone is a potential suspect. And because there’s a killer on the loose, everyone is also a potential victim. Deep in the story, we often wonder which of our fictional friends will be next to fall.

The doubt that builds when we consider who will still be standing at the end adds to our enjoyment of a well-crafted tale. Sometimes this alone keeps us intrigued. Reread Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None to see what I mean. And adding doubt about the protagonist surely helps. This may be one reason why we prefer flawed characters. The best Sherlock Holmes stories are the ones in which narrator Watson wonders if his ingenious friend will be able to solve the puzzle of the day. Because he doubts Holmes will succeed, we do too. And isn’t that part of the fun?

In today’s best crime fiction, it is common for the protagonist to experience self-doubt, particularly if he or she is an amateur or private detective. My fallible private detective Hannibal Jones is wrong often enough that you are justified in doubting if he will ever figure out whodunit. This is required for you to feel welcome relief when he wins out in the end, always through intelligence, strength or another positive trait.

Oh, you say you doubt me? Well, pick up a good mystery story and see for yourself.

Maybe some list-makers were listening to people such as Austin, my mom and me. One of the books shortlisted for the 2011 Man Booker Prize for Fiction, AD Miller’s Snowdrops, places a dead body on the first page. “In Russia there are no business stories,” a character later says. “And there are no politics stories. There are no love stories. There are only crime stories.” The Booker chair was Dame Stella Rimington, a former General Director of the MI5 turned spy fiction writer. Commenting on all that year’s selections, she said, “We want people to buy these books and read them, not buy them and admire them.”

She and the jury were roundly criticized for their emphasis on readability. So what was the response the subsequent year, when the jury was chaired by Sir Peter Stothard, editor of The Times Literary Supplement? He announced that the 2012 winner was Hilary Mantel for Bring Up the Bodies, making her the first woman and first Briton to ever win the prize twice. Not exactly for a mystery, crime or spy story, but along the same lines.

Austin S. Camacho was born in New York City and grew up in Saratoga Springs, NY. He majored in psychology at Union College and, in his varied career, did a 13-year stint in the US Army, where he learned broadcast journalism. He now lives in Northern Virginia, handles media relations and writes for military newspapers and magazines and teaches writing at Anne Arundel Community College. He has authored five novels in the Hannibal Jones mystery series and two others in the Stark and O’Brien adventure series. Some of his short fiction appears in four Wolfmont Press anthologies, and he is featured in Frankie Y. Bailey’s African American Mystery Writers: A Historical and Thematic Study.

Notes:

- John le Carré was nominated for the Man Booker International Prize, which recognizes an author’s lifetime contribution to fiction, but asked to be removed from the shortlist. “I am enormously flattered to be named as a finalist of the 2011 Man Booker International prize,” he stated. “However, I do not compete for literary prizes and have therefore asked for my name to be withdrawn.”

- For more from this online series, see “Delighting in Doubt: Deceptive Art.”

Pingback: Call for the Dead, John LeCarré (Signet, 1962 {Penguin Audio, Narrator: Michael Jayston}) | The Archaeologist's Guide to the Galaxy.. by Thomas Evans

Laura Shovan

One of the best mystery series I’ve read in the last few years is Russian author Boris Akunin’s detective Erast Fandorin. The first book — The Winter Queen — full of suspense, violence, and beautiful writing.

LikeLike

Ilse Munro

Thanks, Laura. I wasn’t aware of this writer. Here’s a description of The Winter Queen for others who might be unfamiliar with this historical detective novel: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Winter_Queen_(novel).

LikeLike

Pingback: Book Review | ‘A Man’s Head’ by Georges Simenon « Wordly Obsessions

Pingback: A Murder of Quality, John LeCarré (Penguin Books, 1962 {Penguin Audio: Narrator: Michael Jayston) | The Archaeologist's Guide to the Galaxy.. by Thomas Evans

Ranjita

pls give the summary of the short story the mother

LikeLike