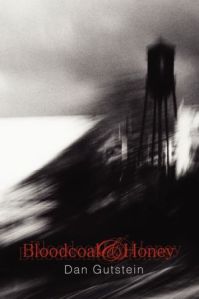

When I find myself unaccountably crying as I reach the end of a collection of poems, when the combined weight of the poet’s felt human presence and the loss seeping through the poems brings tears, I know something powerful is about. This happened as I read one of the last poems,“The Last Out,” in Dan Gutstein’s Bloodcoal & Honey, which I finished while on a long bus journey.

The last time I remember tears burning at the end of a book of poems was when I read Marilyn Hacker’s Love, Death, and the Changing of the Seasons. The ambush was easier to understand: Hacker’s sonnet sequence tells the story of a love affair from birth to breakup.

I was more surprised to feel a lump in my throat with Bloodcoal & Honey. Although many of the poems paint human affection and loss with skill, just as many are forays into surrealism, verbally stunning poems that are obscure in meaning and feel to me like odd objects behind a gate that few readers may be able to penetrate. This isn’t a criticism of the collection. But it is a fact that lots of poems there have bizarre, disjointed imagery and syntax that doesn’t gel around anything real and that surrealism isn’t my thing. Yet, somehow, I mostly loved the book. Gutstein is a really interesting poet.

Many surrealistic poems are fantastic in their pure sound, such as this from “the chance”:

never let it be said that fields change. the smallish pumpkins

are sunken crowns. the stolid headstones, tablets of law.

where the wood gives a deep stand, the spotted deer glance

marbles a bound. where the wind’s raw palm thumps the season.

They alternate with poems that provide a solid sense of the speaker–his feelings and sharp, quirky perceptions–and the emotional situation. That’s where sadness seeps in.

The backdrop of Bloodcoal & Honey is the random alleyway murder of a man named Warren, someone close to the poet. Although only six poems center on the murder and criminal investigation, a sense of things being heavy, grim and out-of-joint pervades the first section. (Six poems in the last section of the book concern the death of Gutstein’s brother and take on a gentler mournful tone). It’s not a depressing read, though, because the writer’s voice feels like company and because he, the grieving survivor, so intensely observes and interacts with the world around him as he goes about his business.

It’s clear how ragged grieving is: thoughts of Warren and the shooting, which the speaker didn’t witness, intrude at the most mundane times. In “The Speed Break,” the poet is trying to break a board in karate class:

“Come on, man,” my teacher says. But I’m all stares

at the black knot. Staring, as he concludes, softly, “—Shit.”

A scene I can’t possibly imagine. The gun tapping Warren’s back.

Then a twitch, then a flash. No pain, nothing but a thin mix

curling down the shoulder chunk. A hole in his back. The black knot.

In “The Alleyway Now,” he’s walking in a meadow with a friend:

…as I turn and see you

hipdeep, a stalk between your teeth.

You call my name, Daniel.

I tilt my head, thrust my hands toward blue.

If I could fabricate, I’d say, yes,

I heard footsteps, a gun clatter off brick.

I followed blood drops behind a dumpster

where I found Warren, a hole in his back.

A lamp came on in the alleyway.

Night had moon but no color, shots but no rescue.

If I could fabricate, I’d say, yes,

I cradled his shoulders.

The title suggests that the alleyway of the shooting is within the speaker at every moment. That’s fitting because these poems are urban. There’s an edginess to them. Even when we can’t be at all sure of the situation or story, we know we’re in a city spot, a gritty one. In some poems, details show we’re in DC. Gutstein seems to be fascinated with hidden corners of the urbanscape, especially anything industrial, low-tech or decaying:

Filmy

here as in tonnage of diesel,

a transformer humming sidewise torsion.

Loopy flowers unbuckle beside barbed wire.

(“Industrial Island”)

A crowd grew across the street from the wrecking ball, which thumped the dying hospital further into a spaghetti of rebar and boxy rubble.

(“Redoubt”)

I liked the book’s eclecticism, and I wasn’t the only one. How depressing to plough through a new collection and find 45 poems from the same mould. Not here! There are prose poems, anecdotal poems, unidentifiable stanzaic forms, lyrics, stuff smacking of “language” poetry and more. Still, techniques characterizing Gutstein’s voice permeate the poetry: language heightened by unusual, juicy word choice; a tendency to write in fragments; vivid images that don’t quite coalesce into a unified scene; phrases repeated unsettlingly. A touchstone mood: besides loss and urban grit, missed human connections.

In considering why reading Bloodcoal & Honey feels glorious rather than sad, I’m reminded of something Harriet Barlow, Director of the Blue Mountain Center, said to me: “Poems about sad things aren’t depressing. Meaningless things are depressing.” Gutstein’s poems never feel meaningless, opaque though some may be.

It was gratifying to see that the local Washington Writers’ Publishing House awarded Bloodcoal & Honey the 2011 poetry prize and is still publishing gems.

Online editor’s note on the author, lifted from his site: Bloodcoal & Honey is Dan Gutstein’s second collection of writing. His first, non/fiction, was published by Edge Books in 2010. His writing has appeared in more than 65 publications, including Ploughshares, Denver Quarterly, Ninth Letter, The Iowa Review, The American Scholar, The Penguin Book of the Sonnet: 500 Years of a Classic Tradition in English and The Best American Poetry, 2006 as well as aboard metrobuses in Virginia. He has received awards from the Maryland State Arts Council, University of Michigan, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and other groups. He works at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) and served as Visiting Assistant Professor in creative writing at The George Washington University. He was named the 2010-2011 “hottest” professor in America by Rate My Professors, and his body temperature has risen accordingly.