When artist Matthew Rice — professionally known as Mateo Blu — was in second grade, he dropped out of school to become a street corner pusher. His drug of choice was candy and he made a mint before his mother caught wind of his escapade. She promptly enrolled him in another school. This was one of many stories Rice told me during our time together this past January, but it was his first question to me which seemed a true testament to his character.

“How’s your son? Is he keeping up with his artwork?” Rice asked me, pulling away from our welcome hug.

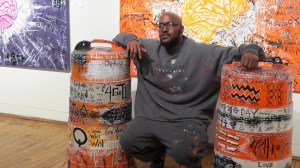

We met at the Eubie Blake Cultural Center in downtown Baltimore so I could view an exhibition of Rice’s work. He’s an imposing figure who stands at six foot four, head smoothly shaven. The gray sweats and basketball sneakers he wore were paint-splattered. Even his fingernails showed evidence of recent work.

Rice and I had met twice before. The second time, my son, who is an artist and also on the autism spectrum, brought his art portfolio along to share with Rice. Although hundreds of people were present and Rice was selling his work, he took time to focus solely on my son and that portfolio, giving advice and encouragement. That memorable interaction set him apart, and I wanted to learn more about him.

The Eubie Blake Cultural Center on North Howard Street might be missed if one wasn’t looking for it. Trash blows along the gutters on the backside of the University of Maryland’s medical school, and the wide avenue is bisected by light rail tracks. Inside, one is greeted with a warm welcome by a man wearing a muted dashiki. The space is divided into two major areas: to the right, a collection of Jazz-era memorabilia and to the left, gallery space.

Rice urged me to look around the gallery while he and his assistant begin taking inventory. The show, twice extended, ended the next day and Rice had to select pieces to be shipped to Arizona for the Smocks & Jocks fundraising event to benefit the NFL Players Association. He selected four or five pieces, one of which was titled, “Breaking Through,” acrylic on canvas, 2012.

The gallery, well lit with a combination of natural and track lighting, had an old warehouse feel to it. The wide-plank wood floors were honeyed with age. On the walls of two rooms, Rice’s paintings hung in vivid hues of royal blue, shocking orange and stark white contrasted against black and shades of gray. Monolithic traffic cones festooned with modern hieroglyphics stood in the middle of the main gallery.

We sat down together, near his painting called, “Seizure.”

“I got kicked out of every school I ever attended,” Rice began, his dark eyes downcast. “Teachers told me I was stupid. They kept trying to put me into special ed where I didn’t belong.”

As Rice recounted his story, he stared at the ground, his giant hands folded between his knees. Most everything he learned in those early years, from reading to multiplication tables, was self-taught. “I wanted to be an engineer, but I was terrible at math.”

Rice, who was born in 1982, lived with his family in East Baltimore. His early years were turbulent, a combination of school troubles and neighborhood challenges. The Rice family was loving and deeply spiritual, but what further separated Matthew from his peers was the talent he displayed on the football field.

“I was one of the lucky ones. My family moved to Prince George’s County [MD] for my last two years of high school where I played football for Eleanor Roosevelt High.”A charter school, Roosevelt focused on academics, and he had to prove his worthiness there. Rice credits this move for putting him in a position to attract a collegiate scholarship to play for Penn State University, where athletics took a backseat to academics.

But the shift from the inner city atmosphere to the farmlands of central Pennsylvania was a culture shock – in more ways than one. For the first time, he found a place where he could – and did – thrive, academically and artistically. When Matthew graduated from Penn State in 2005, he did so with dual majors in Integrative Arts and African American History. From there, he was drafted and spent several years in the NFL before being sidelined with a career-ending, but life-saving, injury. A brain tumor was successfully removed, but Matthew still deals daily with its results: epileptic seizures.

LPR: You attended Baltimore City schools in the 80s and 90s, as a struggling student. What was that like?

MR: I knew I could learn, but I couldn’t do it the way they wanted me to. The overall mentality of the city school system didn’t prepare me to be global contributor or set me up for success. They thought I was stupid. I acted out. I basically taught myself.

LPR: Well, clearly you must be smart. [Baltimore Colt and Hall of Famer] Lydell Mitchell says that you have to be smart in the classroom to be smart on the football field. What was it like for you to go from this place where you felt like you were stupid to rigors of Penn State?

MR: Moving from Maryland to Happy Valley, that was surreal. All that studying after a hard day’s practice. Joe [Paterno] didn’t recruit dummies. For the first time, I started to think maybe I just learned differently. I’d taught myself for so long, but at college I didn’t have to do that.

LPR: Tell me a little more about your college experience.

MR: I chose to stay at Penn State during the summers rather than go home so I wouldn’t get into trouble. Studying African American history, I became of student of American history, and of life. Also, for the first time, I didn’t have to borrow paper when I wanted to draw. I had access to art supplies. I didn’t want to leave that!

LPR: As a senior, you had your artwork selected for the football season calendar, which got a wide distribution.

MR: [Penn State Director of Branding & Communications] Guido [D’Elio] saw what I could do and made my piece “Bluprint” the poster for the 2005 season. That was cool.

LPR: Let’s fast forward. You’re in the NFL, you get injured and and hear that you have a brain tumor.

MR: That was hard. Saved my life. It’s like I finally could grow and learn to be myself.

LPR: Do you miss playing football?

MR: I miss the lifestyle. And the fun. I enjoyed tackling, hearing the crowds cheering. Being on the field, you feel a thrumming in your body.

LPR: What do you miss most?

MR: (A grin spreads across his face) When I played in the NFL, I had a personal chef. He would come in every other week and plan my menus with me. My refrigerator and freezer would be full of healthy things I liked to eat, so I was never hungry. Man, this is some kind of therapy session.

LPR: Don’t worry, there’s no charge. I’m fascinated by your work, which is like Stuart Davis meets street art. You often use dollar symbols and dates in your work. Are these significant?

MR: Yes, the dollar signs are me making a societal statement about money. Instead of people seeing it for the tool that it is, most people view it almost as a religion of sorts. We need it, but we don’t need to be owned by it. And the dates represent important events to me. For example, in “Focus” two of the dates are when my brother was incarcerated and then when he was released.

LPR: And the tally marks? They’re included in nearly every work.

MR: They represent the number of seizures I had while working on that particular piece. At first, I did it unconsciously so I could just keep track, and then it just became a thing.

LPR: Do you have a particular artists work you admire?

MR: God is the greatest artist of all, but Roy Lichtenstein was the inspiration for my mural work in Lubbock and Tuscaloosa. I like Aaron Maybin, who was also a [Penn State] teammate. [Aaron Maybin was a 2006 graduate from Mount Hebron High School in Ellicott City, MD.]

LPR: How about inspiration?

MR: My mother, my father, my family. God. They all inspire me. My mother, in particular, is my hero. She battled breast cancer twice while I was at Penn State and she struggles with kidney disease now. She’s a strong woman, a teacher who will speak candidly about problems. I take a long view of life, and her challenges give a whole different hue and meaning to me.

LPR: After all you’ve been through and continue to experience, you choose to stay in Baltimore. Why?

MR: I want to draw attention to the city, especially to the kids and the educational challenges. I want to produce work and affect positive change before my time [on earth] is done.

LPR: How would you like to affect change?

MR: I escaped poverty and ignorance, some by teaching myself, some by my talents. I want to help lift others up. Especially kids. I want them to have someone who believes in them and helps them believe in themselves. Through my foundation, I visit schools to teach art and hold classes.

LPR: Kids need positive role models, and your story of overcoming adversity is a wonderful example. I’ve heard that some artists have a hard time parting with their original work, feeling like it’s never really finished. Is that true for you?

MR: I have hundreds of pieces, many in series. But I do sell originals – I like to eat! There are the murals, plus many are in private collections, or at businesses, both in the states and in Europe.

LPR: Have you have a favorite piece?

MR: I haven’t created it yet.

Online Editor’s Note: Matthew Rice can be followed on Twitter at @MateoBlu and more of his artwork can be viewed at www.mateoblu.com.

djdnmagney

What an inspiring and remarkable man! Thank you.

LikeLike

Pingback: Seizing Each Moment for Change – RipCord Communications, LLC