I’ve never been to Beijing, so Meg Eden’s invitation to take a trip there via poetry was exciting. My exposure to Eden’s poetry, particularly her collection The Girl Who Came Back (which draws heavily on the Enchanted Forest, a dilapidated abandoned amusement park in Ellicott City) made me feel confident that even in a foreign land she would guide me with an expert eye to the private, hidden, and silent features that define the places I’ve known.

I’ve never been to Beijing, so Meg Eden’s invitation to take a trip there via poetry was exciting. My exposure to Eden’s poetry, particularly her collection The Girl Who Came Back (which draws heavily on the Enchanted Forest, a dilapidated abandoned amusement park in Ellicott City) made me feel confident that even in a foreign land she would guide me with an expert eye to the private, hidden, and silent features that define the places I’ve known.

Eden’s Beijing is a woman expending outrageous effort and demanding complete control for the sake of her appearance, heightening the stakes of Eden’s attempt to take a candid look at her. But Eden does not shy away, leading the collection with “A List Of Banned Chinese Social Media Search Terms,” which additionally serves a short list of themes that seem constantly just behind the lips of Eden’s Beijing as she says, “there are some things that shouldn’t be talked about.” She proceeds to lead us on a tour of Beijing’s bedroom where bras and other sundries litter the floor.

However, the strongest moments of the collection aren’t Beijing’s moments of vulnerability, but the speaker’s own. Through the collection, Eden’s speaker moves from a position of enthusiasm and excitement to disappointment to distance and detachment. The language that accompanies these transformations is insightful and inventive:

If we are name-stealers,

then call me Wendy Zhang.

Let me be twenty poets.

Let me run whole-heartedly

through pavement-seas

with this dangerous freedom.

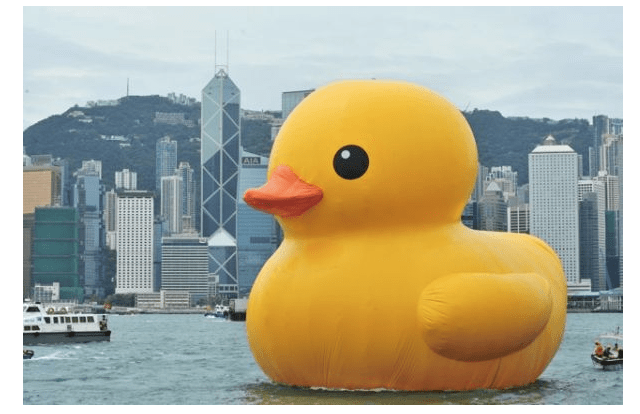

From the picture Eden paints, I would be disappointed too. Beijing, both personified and as a setting is dirty, mean, judgmental, and inconsiderate. Inhabitants of the city are hustling bootlegged CDs, bootlegged restaurants, and bootlegged theme parks (the phrase “copyright infringement” appears twice in three pages). But these are many of the same pictures painted by American media, which reminds me that in reading this collection I haven’t really left the US at all. At times Eden constructs scenes that feel uncomfortably close to stereotype. I have no point of comparison to know whether Eden’s representation is accurate, and if it is then more power to her for having courage to broach the uncomfortable (which is explicitly mentioned in the dedication), but I felt like some poems weren’t giving me the whole story, that there was a side I wasn’t seeing. For example, despite the mentions of “infringement” there was no discussion of shanzhai.

Florentijn Hofman’s contemporary pop-art icon Rubber Duck was copied several times over by shanzhai artists (Photo: http://hyperallergic.com/75107/how-pop-art-got-ripped-off/).

One pair of poems particularly felt like a missed opportunity in this respect: “A List Beijing Composed Of Her Phobias” and “A List Of Beijing’s Discovered Phobias”. The former is totally blank. The latter includes “the young and their lack of fear,” “foreigners and their voices,” “the uncovering of infringed dolls,” and “the compounding of questions.” Both poems are exciting conceptually in allowing space for Beijing to speak both on and off the record, and while they are sharply executed in their current form, both poems seem dominated by the common American conception of China. The first poem a Chinese wall, the second implicating the communist goverment’s efforts to expunge the relative social and economic freedom of the West. But China is more than its government, even if Beijing is the seat of power, and I’m left wondering what the “the young…the derelict…the disabled” of Beijing are afraid of. We never hear from them except as objects and images.

In spite of this limitation, Eden’s eyes would give the government good reason to be afraid. Another pair of powerful poems will likely double as beautifully worded journalism for many readers, myself included. Eden works imagined quotes and quotes reimagined into twin reports on the harrowing details and broader socioeconomic context of a factory fire. And in these twin poems, Eden’s careful wording deftly lays out the facts of the tragedy, in this case creating space for the reader to navigate the confused and complicated structure of Chinese society.

Meg Eden’s work has been published in various magazines, including Rattle, Drunken Boat, Eleven Eleven, and Rock & Sling. Her work received second place in the 2014 Ian MacMillan Fiction contest. Her collections include “Your Son” (The Florence Kahn Memorial Award), “Rotary Phones and Facebook” (Dancing Girl Press) and “The Girl Who Came Back” (Red Bird Chapbooks). She teaches at the University of Maryland.