The “Concerning Craft” series introduces Little Patuxent Review contributors, showcases their work and draws back the curtain to reveal a little of what went into producing it.

Please meet nonfiction writer and essayist, Sue Eisenfeld, whose essay “Wild Feast” appeared in our Winter 2015 Food Issue. Sue’s writing has also appeared in the New York Times, Gettysburg Review, Potomac Review, the Washington Post, the Washingtonian, and many other publications. She teaches for the Johns Hopkins University MA in Writing and MA in Science programs. And now, Sue Eisenfeld:

“Strange seizures beset us,” Annie Dillard wrote in The Writing Life, followed by the affirmation of and permission to write about “your fascination with something no one else understands.” In fact, she says, the reason no one has written “about that idiosyncratic thought you advert to” is: “Because it is up to you.”

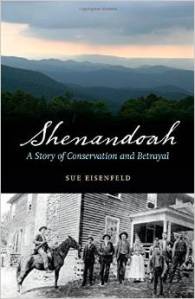

And so it was that I decided to write Shenandoah: A Story of Conservation and Betrayal, featuring my weird obsession: finding historic cemeteries and other relics in the woods.

And so it was that I decided to write Shenandoah: A Story of Conservation and Betrayal, featuring my weird obsession: finding historic cemeteries and other relics in the woods.

This interest started during my childhood in Philadelphia, where my mom brought me to Independence Mall, the historic house of the future Dolley Madison, the basement home site of Benjamin Franklin, and the Christ Church Burial Ground where Franklin and other founding fathers are entombed. That was where I spent my weekends in the 1970s reading every last acid-rain-washed marble tombstone, line by line.

After I moved to Virginia in 1992 when I was 21, my colleagues brought me to Shenandoah National Park my first weekend. It was there I found, over what would become more than 15 years of hiking, camping, and backpacking, that there was a story—a backstory—sketched upon the landscape: old rock walls, stone house foundations, stone piles from farming, and fieldstones in old graveyards. One time, my husband and I set up our tent in the backcountry only to discover that it was situated in the middle of the outline of an old chestnut log home.

Who were the people who used to live here? I wondered. Why had they left? Where did they go? I hiked in that park year after year, on trail, off trail, searching for these sites, wondering about these finds, before it would dawn on me to write about the quest I had become entwined in, discovering and understanding the story of how Virginia used eminent domain to evict residents and create Shenandoah National Park (SNP).

A mentor once told me that when selecting a topic for a book, you should plan to live with it for at least five years. Back then – in my mid-30s, with no real hobbies I could identify and still struggling to find myself as a person and as a writer, I wondered what I could possibly be interested in enough that I could live with it for five years? I felt I led kind of a boring—or at least ordinary—life. Then, because I happened to be reading A Walk in the Woods by Bill Bryson, because I love outdoor adventure and hiking stories, it dawned on me that maybe I should write about what I had been doing for fun for more than a decade: plunging through the trailless backcountry backwoods of SNP looking for signs of the hidden history, the people who had been living there for 200 years before being forced to leave.

This activity was so multi-faceted that I wouldn’t have to live with just one monolithic thing for five years, I realized; this story involved human history and historic maps and hiking and natural history and geology and federal park history and Virginia history and all kinds of nuances I never imagined I’d have to delve into, like calculating the longitude and latitude of properties to determine locations of boundary lines and other esoteric endeavors.

It would be many years into the writing the book that I would come to understand that this backcountry bushwhacking thing that I did was my hobby, something legitimate, even though it doesn’t have recognizable name and most people don’t know what the heck I am talking about or find it a strange pursuit. A few others enjoy doing it too, and I formed a group of friends around this activity. Recently, I have found compatriots in this hobby on Facebook and in a local hiking organization. It is, I came to realize, the idiosyncratic fascination that Dillard referred to. She says that a quirky interest like this “is hard to explain because you have never read it on any page,” and, as if directly to me: “You were made and set here to give voice to this, your own astonishment.” Back when I decided to write a book about this activity and the answers my research uncovered, all I knew was that when the writing sages say, “Write what you know,” this is the kind of thing they must mean.

Online Editor’s Note: Sue will be speaking about her research at the Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) Conference in Minneapolis on April 10 and reading from her book at Johns Hopkins in Washington D.C. on April 17. See www.sueeisenfeld.com for events and other information.

clarinda harriss

I can readily understand how the “odd hobby” led to reflection and writing. This fascinating piece ratchets up my ongoing regret at never havng “done anything with” the graveyard for the poor–the indigent, and evenually tne nameless–which is bordered by Bosley Ave. in Towson, between York Road and Joppa Road–on your right, if you’re going up the hill toward Joppa. When I lived in Towson, my children and I would sometimes picnic there and look for names. There were no gravestones, only short lengths of pipe to indicate where people lay; some had metal markers, very much like markers you can buy to identify herbs you’ve planted, which held paper (?) cards with names written in pencil. The names were almost unreadable. Since the graveyard was adjacent near an old African-American church (now spiffily rebuilt), I assumed that those buried in the field were African-Americans. I tried to figure out a Towson University course (I taught at TU for 40 years) which could have students research the graveyard and its occupants, and I offered to help write a grant for “revitalizing” (funny word in context) the place with the help of that hypothetical class, but nothing came of my efforts. I should’ve tried harder. And should have written about the place long ago. Thank you for jostling my memory with this movng and valuable essay..

LikeLike