A mathmetician, collectivist and so much more, Marc A. Drexler gives perspective to what shapes his poetry and specifically, the inspiration behind his poem in our summer issue, “A Few Blocks” in our latest interview.

Little Patuxent Review (LPR): If your writing were a shape, what shape would it be? Why?

MD (Marc Drexler): This is my poem. I found it inside my head while I was walking. If it were a color, it would be purple. If it were a shape, it would be a Klein bottle.

I also thought about an octagon. I have a poem that is an octagon. I definitely like symmetry in my poetry, but I also think that the essence of shape has to do with how a poem is connected to itself, and how it is connected to other things. So a Klein bottle is enigmatic, both empty and all-containing, because the notion of inside and outside is overturned.

That is how I see poetry in relation to prose. The rules of grammar no longer apply, words are no longer words, everything is a tool to communicate something visceral, or esoteric, or insightful, that prose can’t really handle. Euphony, rhythm, rhyme, polyptoton or whatever rhetorical device all serve the idea and the ideal of communication, the creation of a response in the reader that is unlike an attempt to communicate facts or traditional information.

Little Patuxent Review (LPR): What things, places or people inspired your poem, “A Few Blocks?” Lay out the inner workings of where you were and how you came to create a scenic image for the readers.

Marc Drexler (MD): This was an April poem, from my fourth year doing a poem a day in April, back in 2015. I really like how the pressure to come up with something, good or bad, in some finished form, motivates and inspires my writing. It pushes me to try different things.

I was in Iowa at the time. My mom had died a year previously, my father had moved to a “senior living” apartment the year before that, and I was staying in my father’s house which I was also letting a friend who was having some life struggles live in, and visiting my father most days for either lunch or dinner at the Bickford, and maybe at that point occasionally taking him out places as well. Glenn, my sometime housemate when I was in Iowa, had been given my father’s car to use because his was kaput, and often took my father places when he was still able to get out.

My vague memory was that I thought I would write a poem from the point of view of a dog that day. That is what a poem a day in April does to you. I will occasionally resort to grabbing prompts from the web if I get stuck, but I like to come up with my own ideas for the most part. Even when I write from prompts I tend to do it slant, so I won’t be doing the same thing as everyone else in the workshop, or whatever setting I am in.

I write all my first drafts in an unlined blank page journal, or occasionally on scrap paper if I am inspired when I don’t have my journal with me, but then I transfer my notes to the journal later on. Usually I just open my journal and start writing words down, and see what happens. Sometimes I will get an idea and work on it a bit, but then lose the inspiration, or realize that what I have is some nice lines, but with no real idea behind it. Often I have multiple starts, and sometimes I can use the false starts later on when I have the luxury of a more natural pace of composition. I always keep in mind Frost’s admonition that a poem “begins in delight and ends in wisdom”. But I most often don’t discover the wisdom I am heading toward until some way through the poem.

Anyway, I had the idea to write a poem from the point of view of a dog. Smell is the primary sense for a dog, and I was going to try to put the idea of a scent as I imagined a dog sensing it into human terms. And I had been cooped up inside and hadn’t managed to write anything that day, so I took my journal and went in search of inspiration. At least three of my best poems have been written on walks which I began with the intent of writing something.

The dog never actually made it into the poem, though, because I came up with the structure in the first stanza I wrote and fell in love with it. But then I didn’t want it to be too repetitive, so I started varying the second thing, and kept the color comparison, which really does go back to the original notion of a dog. Dogs don’t see color, and a human’s sense of smell compared to a dog’s is probably very much like black and white vision compared to color vision. And the idea of smell as primal, which can mean first in importance, as it is for a dog, or primitive, connected to origins, which it is for people still resonates with the original idea. Smell has a power we try to recreate in poetry, to evoke some previous emotion in a way words struggle to do. So the ideas of these disparate things, evoked as ideals by a scent, got into my head.

I actually went back to my original notebook from 2015 last week because some friends were asking about the evolution of this poem. The original form was much like the final form, written directly in my notebook, in six prose stanzas as they ended up, as I actually was walking around Ames, Iowa, near my father’s old house.

At that time they had torn up a large section of Hayward Avenue by the Ames Intermodal Facility (long name for a bus terminal), which is where the smell of the earth came into it. The magnolia I think wasn’t right there, it was something I remembered from earlier, but was a good starting point. There may have been a juniper, but it also may have been a walnut which I changed to a juniper. I habitually pick juniper berries and sniff them as I walk if I pass a shrub, and also do that with walnuts I find fallen. The ink blotch and the anise were actual smells I encountered randomly, or maybe not so randomly for the ink blotch.

With the ink blotch I think I was influenced by Frank O’Hara, too. I had discovered him a couple of years before in ModPo, and was enchanted by the way he combined the poetic and conversational in the natural way he does in his Lunch Poems, being the narrator, but also being part of what is being narrated at the same time, with his feelings coming into the poems, and his friends, and his random gifts to his friends, which is really what those poems are about. At the time I wrote the first draft of this I was reading a lot of O’Hara.

ModPo asserts that all poems are metapoetic, since they are all written by poets, and no one can entirely keep themselves from what they write even in more impersonal verse. So part of this poem is about the ink used to write it, which is a little Klein-bottle-ish.

Amusingly, after having this poem sit around about five years without my really liking it that much, on one revisit I noticed I had used the word “hint” five times, all in different stanzas, in describing the smells. After I excised all but one of these, which involved some serious rewriting for structure, as well, I kind of fell in love with the poem again. (I say again, because I am always in love with the thing I have just written, even if it turns out the next week to be drivel.)

LPR: I did some background research and noticed you received your college degree from John’s Hopkins University in Mathematics. Has math created specific inspiration for your poetry? Are there mathematical equations you use to perfect your poems and writing?

MD:Math, ultimately, is about thinking.

In both math and in poetry there is beauty in elegance.

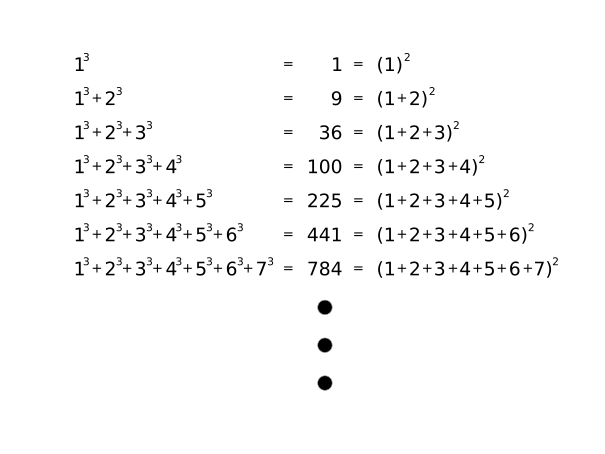

When I was twelve and in 8th grade I was walking somewhere and started adding up cubes of integers in my head. One cubed plus two cubed plus three cubed plus four cubed happens to be 100. I noticed that the sum of the first N cubes was always a square, and in fact, was the square of the Nth triangular number.

This couldn’t be accidental, but it wasn’t something I had ever run across. Luckily, I was enrolled in a program where I met weekly with a math grad student at ISU, so the next time there I shared my discovery, and he showed me how to prove it using proof by induction, which was also fun. So part of math is the proving of things, and the determining what is true, and what is provable, and what we can know. But also, part of math is just discovering the beauty of these relationships, like the pythagorean theorem, or all the strange things that arise from the Fibonacci sequence.

Reading a poem should be like making a discovery of connections like this, on one’s own, at twelve. Not about the proof, but about the truth. Keats (himself quoting the urn speaking in his imagination) said, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

This is to me is the connection between poetry and mathematics. Wallace Stevens also speaks strongly to this in his poem “On the Road Home”

LPR: Going off of the previous question, are there specific philosophical areas of study that have pulled the most inspiration in your life and in poetry? Have they helped to create a sense of self in your work, relationships and life?

MD:The short answer here would be “no”, but that would be boring. And of course, everything in my life has influenced my poetry. Probably the most influential on my life is collectivism, the idea of a group of equals acting toward a common goal. And I guess that is also kind of Whitmaesque, as well.

I suppose the notion of fairness starts with symmetry.

I had progressed rather like an arrow from childhood to math grad school. I was so good at math that I hadn’t ever considered what I wanted to do with my life. I just did what was fun, and that led through Johns Hopkins to the University of Maryland for grad school. Maryland had recruited me actively. I attended an overnight recruiting event with a bunch of other high Putnam scorers my final semester at JHU. Maryland was very strong in number theory, the purest of pure math and the area that interested me the most, so they were already on my radar, and they were close.

Grad school was a disappointment. First, I didn’t like my advisor, or, more correctly, I liked him well enough, but he didn’t get me. He had no understanding of why I needed to get to the main Library before it closed (to look up José Martí’s poetry) when everything I could possibly need was in the Math library.

I loved teaching. My advisor also told me not to put too much effort into my teaching, because my assistantship was just an excuse to give me a stipend. Meanwhile, there were fifty students in two sections who saw only me in their classes, relying on me to teach them according to the syllabus the professor, who taught one section himself, had made. Maryland may have been paying me a stipend to teach, but my responsibility was not to the university, but to my students.

Then, there was number theory. Everywhere else in the world, number theory was the purest of pure math, with no relation to the world. Not so at the University of Maryland.

Maryland’s math department, it turned out, was a farm team for the NSA. Number theory is very useful in coding and codebreaking. So useful, in fact, that I realized that if I ever made a major discovery in the areas I was most interested in, I would have to send it to multiple foreign governments before I could publish it—especially Russia and China—lest it be classified.

That wasn’t anything I needed to worry about immediately, but it was disillusioning. I started volunteering at the Maryland Food Coop, where anyone could work an hour for some food credit, in order to support my Havarti cheese habit. My teaching assistantship didn’t pay all that much, and Havarti cheese is an expensive luxury if funds are short. This was my introduction to collectivism.

Coops are of different sorts. Some are just regular businesses with a group of owners, some rely on membership. The Maryland Food Coop was actually the Maryland Food Collective, a worker’s collective owned and run entirely by the workers, who shared or divided all the responsibilities for the store, and met every Monday to consider issues and policy. Everyone was equal. It was about half students, and half former students. The student workforce turned over rapidly, and was balanced by workers who remained longer. Not even considering the activism, the idea of an environment where everyone was equal, and was equally responsible, was wonderful. I drifted out of grad school and into the coop. I also got involved in the Markland Mediaeval Mercenary Militia, and I started not just reading poetry regularly, but writing it as well.

I should mention that before I started working at the Food Coop, I really had no idea how to interact with people in general. I was too early for an Asperger’s diagnosis, but as a child I had 95% of the hallmarks, the tics, the constant rocking and humming, the awkwardness of never understanding social conventions because they hadn’t been explained in a manual I could read. I had always rebelled against authority, because authority made no sense. It was anti-symmetric, and generally not beautiful. The coop’s review system, allowing worker-equals to raise issues with other worker-equals when there were conflicts allowed me to really understand how other people thought, and why, for the first time, because everything was explained directly. If someone had an issue, there wasn’t an authority to settle it. People needed to work together. And because of the counter-cultural atmosphere in the coop, cultural assumptions were not a shared starting point for everyone else, as they had been in my elementary school and junior high school. It was very freeing. I worked there fourteen years, which was the second-longest tenure of any paid worker at the time I left. I write a lot of personna poems, and I think the fact that I had to study people in order to understand them makes it easier to write in a personna, whether that of another person or an object.

I almost always mention collectivism in my bios, including my memebership in the Earth Collective, a group of roughly 8 billion people who make all the decisions on how we interact with our planet.

When asked where we can find his work, Marc shared that he plans to publish 3 more poems. He also hopes to create inspiration to publish his own book and continue submitting his work to journals. It’s all a writer can hope to have their work published and find community in that work. All of which Marc has accomplished. Being the multifaceted writer Marc is, it is without a doubt that we will see him publishing more of his work and joining aspects of his life and passions into his poetry.