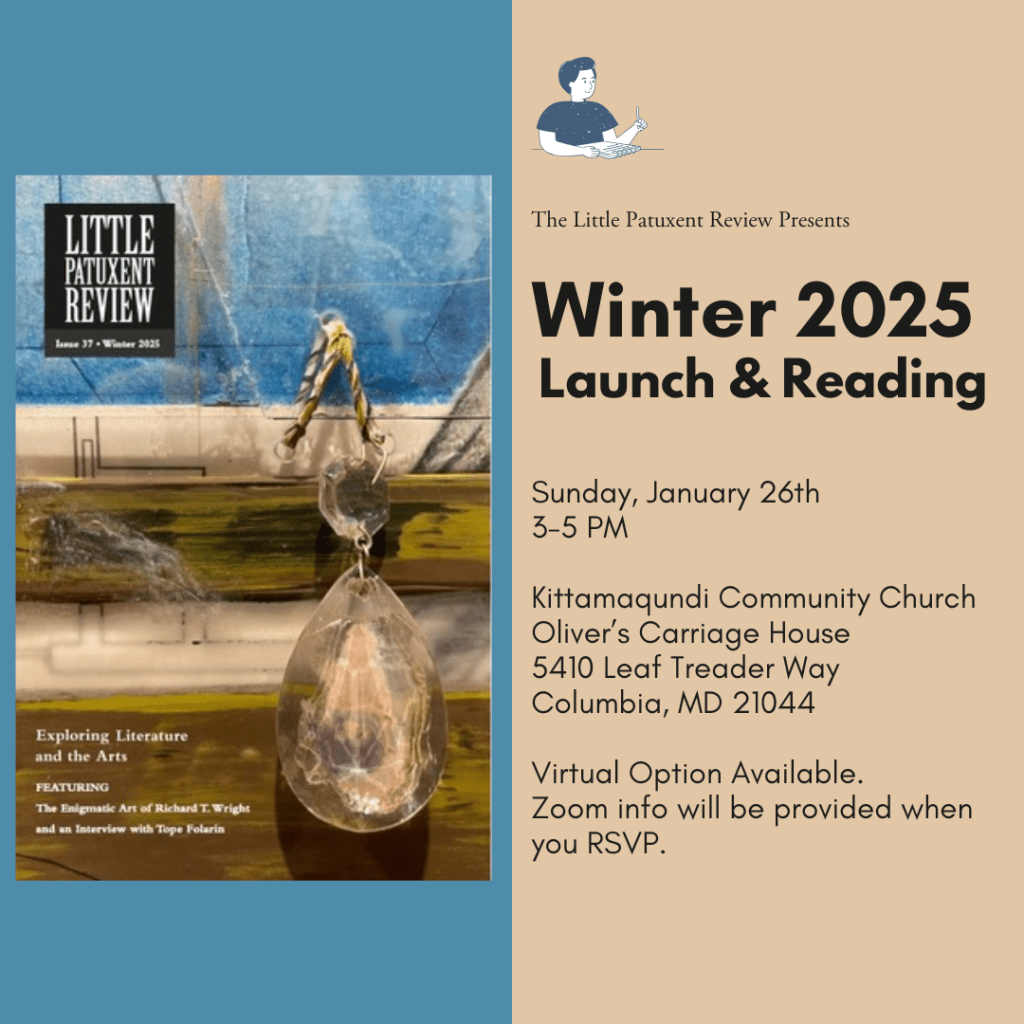

LPR is excited to share our new winter edition on January 26th. Please read ahead for the editor’s note along with which authors will be attending and reading their works at the launch.

In 1941, the French composer Olivier Messiaen composed Quatuor pour le fin duTemps (Quartet for the End ofTime) while imprisoned at the German prison camp StalagVIII-A in what is now Zgorzelec, Poland. The typical quartet texture of the European classical canon was either piano and strings or strings alone (two violins, viola, and cello); Messiaen, however, wrote his piece for the forces available at the camp—or those that could be procured with the help of group fundraising and cooperative guards: piano, cello, violin, and clarinet. The piece was premiered by professional musicians inside the camp to an audience of some 400 prisoners and guards.

I had planned to move on to Dmitri Shostakovich, George Orwell and Ray Bradbury, more artists whose works interacted with or responded to totalitarianism. But I have to stay for a moment with Messiaen. His deeply personal Quartet is full of birdsong and spirituality, an idiosyncratic work in eight movements (rather than the typical four), one of which is titled “Tangle of Rainbows, for the Angel who announces the end of time.”The only political statement of Messiaen’s work of art was that it existed at all; that with a stub of pencil the composer wrote it down at all; that it was performed for a hungry and broken audience, at all.

Professional musicians, and instruments, and sympathetic guards were in that camp.

Artists are everywhere, even in prison camps. Authoritarianism abhors art.

Authoritarianism abhors creativity, critical thinking, empathy, and imagination.

Authoritarianism stands just outside the door of every democracy.

As this issue of Little Patuxent Review is launched, authoritarianism has been ushered right inside. Our democracy in the U.S. is so fragile, so terribly incomplete from its very inception, so tenuous. As a person for whom art lights the way, I hope for the nearly-impossible in the face of anxiety: that we stay as pried-open as we can bear to be; that we keep reading, listening, looking, and identifying each other’s humanity.

This issue of LPR begins with Tim Singleton’s remembrance of the beloved Mike Clark, followed by a commemoration of the 50th anniversary of HoCoPoLitSo.The works of prose and poetry in the issue are varied and marvelously human. There are stories and poems about all kinds of relationships; the natural world; Americans grappling with their sense of American-ness at home and abroad (there are even a couple of Berlin stories); and growth and healing, sometimes after trauma. Indeed, there is some trauma in these pages; please be aware of a reference to sexual assault in the poem “I Knew a Father.” Two wonderful artists are profiled: writer Tope Folarin and visual artist Richard T.Wright. May their profiles here spur you to connect with their art—and all art—in greater depth.

—Sarah Berger

We enter an important time of transition, one that signals the need for more art, creation, and a powerful and grounded stance in our truth. “Your silence will not protect you,” Audre Lorde, “Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches.” Though we live through turbulent times, we hope the poetry and readings found in our new winter edition will inspire you, make you think, and also create your own art.

The contributors who will be at the launch are as follows,

Mirande Bissell, Mouth

Erik Fatemi, Path of Totality

Madeline Izzo, Witness

Mickie Kennedy, Aubade with Peaches, Eggs, and Hissing Garlic Squirrel Hunting

Blair Pasalic, Brood X

Alice Stephens, The Origamist

If you haven’t had a chance to RSVP to either our in person or virtual launch, feel free to do so here.

In Person Attendance

Virtual Attendance